While we already covered the seven worst video game consoles a few months ago, there was one notable omission.

Something that deserved its own feature. Something so embarrassing for Nintendo that, even to this day, it won’t even officially acknowledge its existence… we’re talking, of course, about the Virtual Boy.

By the end of the 16-bit era, Nintendo had found success with both the NES and Super Nintendo, and in 1995 the company was looking to release two brand new consoles. The first was the Ultra 64, which would later release as the Nintendo 64. The second, however, was a unique and innovative stab at the gaming market known as the Virtual Boy. But, despite Nintendo’s previous success, not everything it touched would turn to gold.

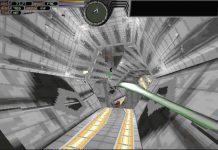

Developed as a somewhat-successor to the original Game Boy, the Virtual Boy was released at a time when “virtual reality” became something of a buzz-phrase in pop culture. In contrast to the NES or Super Nintendo, or other consoles of the time from competitors Sega and Sony, the Virtual Boy stands out. It doesn’t display full colour graphics, it doesn’t require a TV to work, and it runs on six AA batteries (though an AC adapter could be purchased separately). The real gimmick to the Virtual Boy was its ability to produce 3D images using a combination of displays and mirrors to give depth. The user sits at a table with the Virtual Boy, head against the eyepiece, with games displayed in a red monochrome format and controlled via a unique “dual d-pad” controller.

Reflection Technologies, Inc.

The technology behind the Virtual Boy had been in production since 1985. Allen Becker had developed a system of viewing 3D images using a series of red LEDs on a black background and a pair of stereoscopic displays that give the illusion of three dimensions. His company, Reflection Technologies, Inc., or RTI, produced a prototype called the “Private Eye” using a one-inch screen attached to the user’s head. That might seem ridiculously small, but from close range the tiny screen seemed large enough to be workable (think Google Glass, but worse). The next step was shopping the unit around, and RTI began seeking working relationships with companies to both fund and develop the hardware.

Easier said than done. Embracing the very 1980s philosophy of “if your product doesn’t serve any practical or military purpose, flog it to children”, RTI first approached toy giants Mattel and Hasbro who both turned it down. Nobody wanted this weird little red-and-black thing, with the general malaise towards the device being personified no better than in a man named Tom Kalinske. Kalinske was President and CEO of Mattel and, after being shown RTI’s “Red World” demonstration, saw the limitations and showed them the door. RTI next tried to market the device to video game companies – unfortunately for them, during the intervening years Kalinske had been poached to become CEO of SEGA of America. When RTI approached SEGA, it again demoed the technology to none other than Kalinske – who had the pleasure of turning them down for a second time. Things were looking bleak.

It wasn’t until RTI showed the technology to Nintendo that it found some success. Enter Gunpei Yokoi. Yokoi was a Nintendo stalwart, having worked for the company since the mid-1960s. He’d designed the famous Game & Watch device and, as head of Nintendo’s Research and Development 1 division, had found great success with the original Game Boy in 1989. Despite seeing some creative output on the NES and Game Boy, he felt that there was a distinct lack of creativity in games at the time, particularly on the Super Nintendo. What Yokoi saw in RTI’s hardware was something radical: a brand new system that could revolutionise the way video games were played. It reflected Nintendo’s reputation for innovation and, due to the proprietary nature of the hardware, would prove difficult for a competitor to clone.

Nintendo jumps on board

Yokoi was convinced, but no deal was made there. RTI next had to convince Nintendo’s board and then-President (and genuine legend) Hiroshi Yamauchi that the device could be a big player in the video games market. RTI had to pitch to Nintendo yet again, and it was during this second pitch meeting that a sudden “thud” was heard from the back of the office: Yamauchi had actually fallen asleep during RTI’s presentation. While RTI was initially dejected, this was actually Yamauchi signalling his ‘checking out’ of the conversation allowing those below him to make all the decisions – apparently in keeping with Japanese business culture. Nintendo were now officially on board, and the project was a go.

With Yokoi at the helm, development began in 1991 under the project name of “VR32” and would last four years. Certain concessions would need to be made fairly immediately. Yokoi looked into creating a full colour version of the system but found it would cost around $500, far more than a consumer could be expected to pay at the time. The colour version also struggled to display 3D graphics correctly, meaning players would see double rather than any 3D effect. As a result, Yokoi went back to RTI’s original idea of using red LEDs as these were cheap and more easily distinguished on a black background. RTI’s design had originally featured a head-mounted unit, but due to fears of the unknown dangers of EMF radiation and the unit being too heavy, this was replaced with a table-top stand making the device stationary rather than attached to a player’s head.

The stationary unit didn’t solve all the problems, however, as the next hurdle was concerns over motion sickness while using the unit. Virtual reality devices, even the VR units that are used today such as the PSVR or Oculus Quest, often cause the user to suffer from a phenomenon known as “vestibular and visual mismatch”. Essentially, this means that your brain thinks you’re moving when you aren’t, causing all sorts of motion sickness. Not every member of the playerbase was susceptible to this, and some symptoms could largely be mitigated by ensuring the stereoscopic displays were properly aligned before each play session, but it was such a problem that for the Western release every Virtual Boy game would feature an option to pause the console every 15 minutes to remind the user to take a break. When you need to introduce Big Brother-style elements to a console, that’s probably a bad sign.

Despite the drawbacks, Nintendo persevered. In November of 1994 it would officially announce the Virtual Boy with, in hindsight, a rather over-confident sales projection of 3,000,000 units sold in Japan by the end of the first quarter of 1996 (it ended up selling only 140,000 in Japan by the end of the system’s entire life). The first 1994 demonstration was met with less than favourable reviews, with one critic referring to it as the “Virtual Dog”. Hoping on a more impressive Western release Nintendo presented the unit with a simple driving simulator at CES in 1995 and later at E3 that same year, but to equally lukewarm reception.

Hard to market

It finally hit stores in the US on 14th August 1995 for the relatively high price tag of $179.95, though it did include a pack-in title in the form of Mario Tennis. From a promotional standpoint its greatest gimmick became its biggest flaw, with the 3D effect not translating at all well in television or print advertising. Short of finding a demo unit to try out, this limited marketing to more of “please trust us, it does work” strategy that has never really gone down well with new technology. Due to the ongoing development of the Nintendo 64, Yamauchi decreed that the Virtual Boy should not receive a mainline game in the Super Mario franchise so as to not overshadow the impact of the upcoming Super Mario 64. While this seems like it would have been unlikely anyway, it was another nail in the coffin that hampered interest in the Virtual Boy from the outset.

As a result, the Virtual Boy never quite reached the levels of success Nintendo had gambled on. It featured a grand total of 22 games, but as eight were exclusive to Japan that means the US only received a measly 14 – none of which were much to write home about. Notable titles are limited: outside of the prior mentioned Mario Tennis, there’s an incessantly slow and really rather dull version of Tetris in 3D called, unsurprisingly, 3D Tetris – and an entirely different version of 2D Tetris called V-Tetris. For sports fans, there’s an adequate boxing game called Teleroboxer and a form of 3D golf just called Golf. Perhaps most reflective of the system’s quality is the adaptation of stupendous Kevin Costner-starring cinematic flop Waterworld. While these may not whet much in the way of appetite, it did also receive a game featuring Mario’s childhood-friend-turned-cousin-turned-arch-nemesis Wario in Virtual Boy Wario Land, which is the closest you’ll get to a proper Mario game, and a remake of 1983’s Mario Bros. dubbed Mario Clash, which is probably the best that can be expected.

So, we have a console that can’t display full colour, has no mainline Mario, Zelda, StarFox or Metroid, had quite a high price tag and actively made users sick. It’s not hard to see why the Virtual Boy is considered Nintendo’s biggest failure. Sales reflect this, with worldwide figures reaching only around 770,000 units sold – a far cry from the projected numbers. The console actually skipped any sort of PAL/European release, so if you’re looking to pick one up from outside the US you’ll need to pay for shipping as well as an appropriate power transformer. Some users have emulated the console, though as this is mired in illegalities and naturally doesn’t produce the 3D effect that the console was designed for, it’s a rather pointless endeavour.

The Virtual Boy became something of a persona non grata at Nintendo. Over the course of its development, even lead designer Yokoi himself became increasingly reluctant to release it in its existing form and it was eventually rushed to market to make way for the Nintendo 64. A year after the Virtual Boy’s release, Yokoi would retire from Nintendo and join Bandai, spearheading the creation of the Game Boy competitor the WonderSwan (Nintendo denies the failure of the Virtual Boy and Yokoi leaving the company are related). Yokoi tragically passed away as a result of a car crash in 1997 but his work on the Virtual Boy is a testament to one visionary designer and his passion for innovation which, for better or worse, remains an indelible part of Nintendo legacy – regardless of whether or not Nintendo itself wants to admit that.